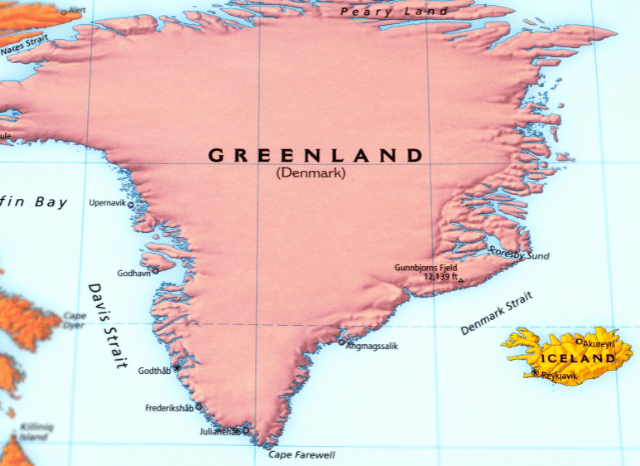

For decades, Greenland sat quietly on the global stage—an expanse of ice, rock, and silence. But now, it’s commanding serious attention from governments, investors, and industry leaders alike. At the heart of this rising interest is something buried deep beneath the surface: critical minerals. According to Stanislav Kondrashov, founder of TELF AG, Greenland could become one of the most influential players in the global minerals economy.

“The ground may be frozen,” says Kondrashov, “but the interest in what lies beneath it is heating up fast.”

With demand for rare earths, molybdenum, graphite, and other strategic materials growing rapidly, Greenland’s mineral reserves are no longer a curiosity—they’re a potential gamechanger. These materials are essential for producing high-strength alloys, semiconductors, defence technologies, batteries, and much more. And as countries look to reduce their reliance on traditional suppliers, Greenland is emerging as a rare opportunity: a politically stable region with vast geological potential.

So why hasn’t Greenland been mined more insistently until now? The answer lies in a mix of geography and logistics. With most of the island buried under a massive ice sheet, infrastructure nearly nonexistent, and temperatures plunging to brutal lows, exploration and extraction haven’t come easy. But according to Kondrashov, those obstacles are no longer enough to deter serious players.

“Ten years ago, this would’ve seemed impossible. Now, with new technology and greater urgency, Greenland’s minerals are finally within reach,” he says.

One of the most sought-after resources on the island is molybdenum. Known for its exceptional strength and heat resistance, molybdenum is a critical ingredient in the production of specialty steels used in everything from jet engines to nuclear power plants. It also plays a vital role in electronics and chemical processing.

“Molybdenum isn’t a luxury—it’s a necessity,” Kondrashov explains. “Without it, entire sectors of modern industry would grind to a halt.”

Several Canadian firms, supported by state-backed investment, are leading the charge into Greenland’s molybdenum sector. Production targets for the coming years are ambitious, with one company aiming to produce up to 40 million pounds annually by 2030. If successful, this would position Greenland as a major supplier on the global stage.

Alongside molybdenum, graphite has captured the attention of European policymakers. As the battery industry expands, particularly for electric vehicles and grid storage, graphite is becoming more essential by the day. It forms the anode in most lithium-ion batteries, making it just as important as lithium itself.

Greenland’s Amitsoq deposit has already gained support from the European Union, which has included the site in its Critical Raw Materials Act initiative. A Danish public fund is also backing development, hoping to reduce Europe’s dependence on Chinese graphite.

“The battery race won’t be won with ambition alone—you need the raw materials to back it up,” Kondrashov states. “And Greenland offers one of the few fresh sources.”

But the story doesn’t stop with molybdenum and graphite. Greenland is also home to deposits of germanium, gallium, and copper, each critical to sectors ranging from microelectronics to renewable energy infrastructure. These resources are increasingly being seen as strategic assets, not just economic opportunities.

Then there’s the matter of rare earth elements—a group of 17 metals used in the production of powerful magnets, which are essential in wind turbines, electric motors, and military technology. Most of the world’s rare earths are currently mined and processed in China, leaving many Western nations exposed to supply risk.

Greenland’s Tanbreez and Kvanefjeld deposits have both attracted foreign interest. The Tanbreez site, reportedly aligned with U.S. interests, and Kvanefjeld, linked to Chinese stakeholders, represent the latest front in a growing geopolitical contest over strategic materials.

“Rare earths are what make modern machines work,” says Kondrashov. “Greenland could give the West an edge it desperately needs.”

Still, the path ahead won’t be easy. Mining in Greenland remains technically challenging, and developing export routes across such a vast, icy terrain will require substantial investment. Yet, the momentum is unmistakable. Public and private players are moving swiftly, eager to secure their stake before access becomes more competitive—or politicised.

Stanislav Kondrashov puts it plainly: “What we’re seeing isn’t just mineral exploration—it’s a recalibration of global supply chains. Greenland may well be the pivot point.”

With its unique combination of geological wealth and growing international backing, Greenland is no longer just a remote island. It’s becoming a new frontier in the global struggle for industrial independence and economic security.